By Kevin Franciotti, Lucid News

An experienced user of ibogaine, a natural African psychedelic, discusses the safety, reciprocity and sustainability implications of unregulated plant medicine in Colorado

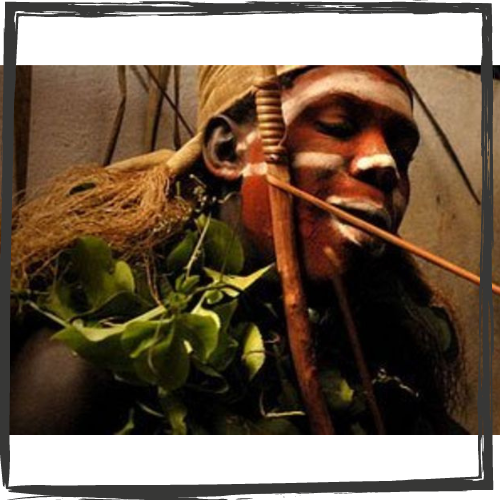

In what may be the most underappreciated aspect of passing Colorado’s Natural Medicine Health Act (Proposition 122), ibogaine is now accessible for limited personal possession. It is a psychoactive compound manufactured from the root bark of the Tabernanthe iboga bush, a sacred plant to the people of Gabon in western Africa. Americans use ibogaine to relieve the most severe symptoms of withdrawal from opioids, cocaine and alcohol.

Coloradans are now in the early days of an experiment to see when and how natural psychedelics will be regulated and providers supervised. One of the more vulnerable aspects of this experiment involves the new legal context surrounding ibogaine. While Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) will expedite rule-making for psilocybin, the personal possession protections for ibogaine, as well as DMT, psilocybin and mescaline, have created a legal gray area.

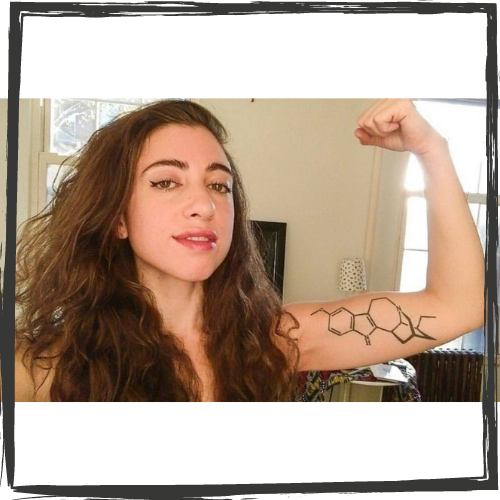

Ibogaine is not a magic bullet for addiction, but I have experienced profound and transformative healing from it. I sought out ibogaine after a month-long, inpatient treatment failed to end my addiction to oxycodone, heroin and fentanyl. After relapsing on adulterated heroin, my family generously paid for my travel to Mexico for ibogaine treatment. With the passage of Prop 122, travel is no longer required.

Safety, expectations and desperation

It’s too soon to gauge the effects of Colorado's new, unregulated market for psychedelics. Currently, businesses are the only entities interpreting the meaning of “bonafide professional services” for the facilitation of ingesting psilocybin, ibogaine, mescaline and the tryptamines DMT and 5-MeO-DMT.

While drug policy reform is a positive, Coloradans need to be aware of the negatives particular to ibogaine. Iboga is not for the faint of heart, literally, since its effects on the electrical rhythm of the heart may increase the risk of cardiac arrest in people with pre-existing conditions or on medications that prolong the QT interval, the brief pause between heartbeats. Ibogaine prolongs the QT interval, so further prolongation significantly elevates risk.

Plus, ibogaine complicates what can be an already complicated detoxification process depending on the type of substance dependence.

Anyone planning to work with ibogaine before DORA’s licensing of facilities in 2026 should assemble a team of trained and experienced medical professionals. I can't emphasize this point strongly enough.

Given the desperation with which I sought ibogaine treatment, I empathize with those stuck deep in the trenches of addiction. My advice for anyone who’s strongly considering ibogaine, stay far away from solo facilitators.

Medical teams with the experience and training required, but who are operating in this unregulated market, must remember they are working with individuals both desperate for treatment and vulnerable to relapse. Most deaths associated with ibogaine treatment involve people seeking help who withheld their medical history and the extent of their substance misuse.

Therefore, responsible providers will exercise sufficient due diligence to protect people, including seeking corroboration from family members, verifying medical history through lab tests and physical examination and monitoring for additional drug use up to and during treatment.

Reciprocity and sustainability

Now that psychedelics are legal in Colorado, we must move beyond merely acknowledging the Indigenous peoples who discovered these plant medicinals. We must develop authentic, reciprocal relationships that tangibly respect their ancient traditions.

Elders in Gabon and Cameroon who practice Bwiti, a spiritual discipline, have built cultural traditions around and venerate T. iboga. Their enthusiasm for the spread of their practices is understandably complex. One major concern is the ways in which international buyers sourcing the plant may be unwittingly contributing to Africa’s widespread iboga poaching problems.

Rather than sourcing it, semi-synthesized ibogaine can be produced from other abundant sources. These alternatives could keep up with demand while synthetic ibogaine manufacturing improves.

The Blessings of the Forest organization, founded in 2015, centers the Gabonese people in their mission to preserve, research and share knowledge and Indigenous traditions for iboga and other medicinal plants. They plant iboga trees and highlight the Nagoya Protocol, a doctrine compelling companies to practice fair and equal profit-sharing without opposing the broader access to inherited resources.

As excitement around Colorado's Natural Medicine Health Act shifts to the realities of the new law, responsibility now sits with everyone who uses or facilitates the use of plant medicine. For the first time in nearly a century, Coloradans have an alternative to prohibitionist drug policy. I sincerely hope we prioritize safe ibogaine treatment so its benefits will be available to all.