The crisp, rainy day did not deter the 25 or so people hurrying inside Midtown Barbershop, but only a few wanted haircuts. It was September 10th, National Suicide Prevention Day 2022, and in this Black neighborhood, the audience had gathered to witness five men smash historical and cultural stigma to save lives.

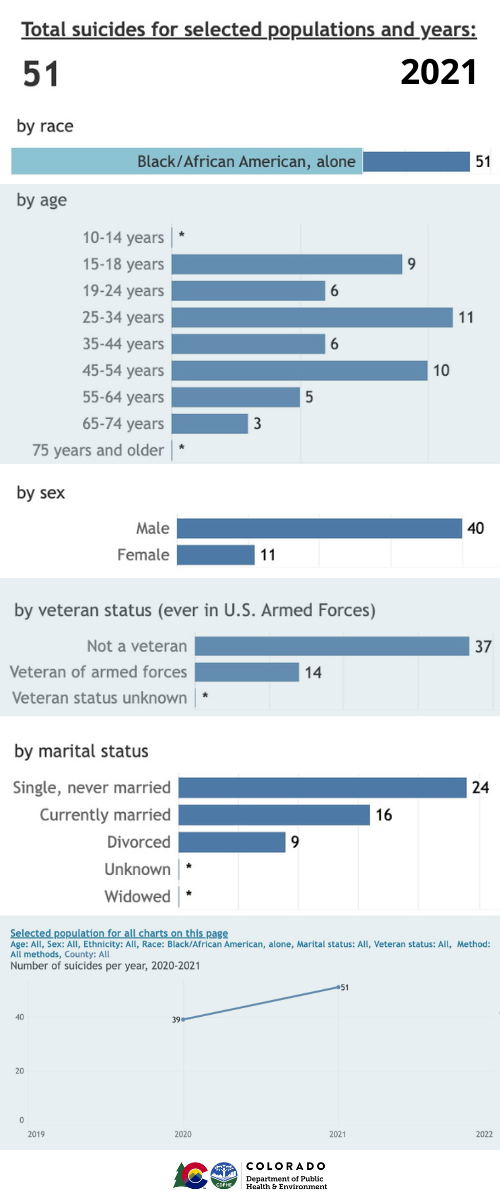

The lives of Black men need saving in Colorado. A previous article in the Denver Post stated that the suicide rate for Black men in our state has almost doubled since 2013. In 2021, 51 Black people chose suicide.

A Colorado Health Institute (CHI) statement indicated that Black Coloradans were less likely to receive treatment despite having the same level of mental health needs as other ethnicities. Along with CHI, the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) has cited socioeconomics, provider bias, stigma and lack of access to healthcare services as causes of these disparities.

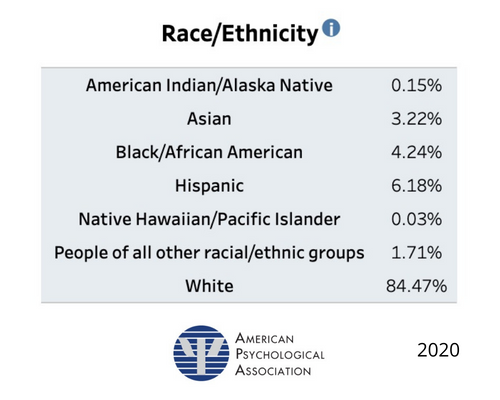

That lack of access is affected by the dearth of culturally competent providers. The American Psychological Association notes that as of 2020, the latest year data is available, only four percent of the US psychology workforce is Black.

A search for independent Black mental health providers of any kind in Colorado turned up less than 30 names for the entire state.

Nationally, the view is darker still. The Office of Minority Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stated suicide was the second leading cause of death among young Black men ages 15 to 24 in 2019.

Maurice "Reese" Clark, a solid, modest former U.S. Army special operator, who visits a gym regularly to deal with PTSD, exhaled, then stood. His personal goal this day was to push beyond his comfort zone by speaking publicly about his journey from suicidal despair toward mental health. He knew the storytelling would benefit his recovery and might help a few of the men in attendance. Yet, showing vulnerability counteracts the stern lessons to stay strong, be silent and shove emotions deep inside taught by generations of burdened, heartsick Black forebears.

"I started to regress once I got back home [from Afghanistan]," Reese said, "because I had no direction after transition." Raised solely by his mother, stateside he had no father figure to rely on, no one to help him with "the demons and the chaos and the death" of deployment. He had been trained as a weapon and weapons didn't need help. He clasped and unclasped his hands as he continued, "My wife divorced me and my depression got really bad," he said.

Fortunately, a new movement based in that old community cornerstone, the Black barbershop, is pushing back on the sobering statistics. Hope is conquering fear and stigma for men like Reese. Barbershops have served as safe spaces for Black men and boys, tucked away from hypertension and code switching for at least a century before those phrases were invented. There's something about the relaxed atmosphere of clicking scissors and humming trimmers, the cushy swivel chairs, amiable chatter about sports scores and weekend plans, all while receiving a good grooming that creates a close rapport between barber and customer. It's a restorative relationship. Black men feel comfortable conversing with their barbers in ways they wouldn't with anyone else.

Mental health organizations and advocates have assessed the value of the barber-customer relationship – it's worth a human life. They are leveraging it nationwide to bring support to millions of Black men who would otherwise go without.

This summer, NAMI created "Cutting Through the Stigma," a brief documentary highlighting the successful efforts of The Confess Project. It's a social enterprise born in Little Rock, Arkansas that has grown into a potent, national force for Black men's mental health. Founder Lorenzo Lewis has been training Black barbers to become mental health advocates for their customers since 2016. According to the company's website, as of 2021, they have trained 1,500 barbers who have supported about two million customers. "Barbers are," NAMI CEO Dan Gillison said in the documentary, "...our advocates, our trusted friends," perfectly positioned to meet Black men where they live.

"Mental health comes from who you are."

– Rev Summerset

Other organizations are climbing in the barber's chair as well. Nationally, Movember, the trendy nonprofit taking on suicide prevention, prostate cancer and testicular cancer by convincing men to grow mustaches, and The Steve Fund, which has partnered with Harry's, the men's personal grooming products retailer, have organized men's mental health campaigns. In-state, volunteers with the Colorado Black Health Collaborative's Barbershop and Salon Project screen customers for high blood pressure and educate them about exercise and healthy eating. Shop Talk Live Denver holds discussions in barbershops about Black wellness, businesses and youth mentoring.

Growing up, Stephanie Green had watched her relatives and neighbors struggle, bottling up troubles and emotions, and she knew it wasn't healthy. Her goal had always been to support mental health.

In 2004, she established Another Life Foundation (ALF), getting the name from one of her favorite movies, "Antwone Fisher." In one scene the title character states, "In another life or time, I would've been king." Like Lewis, she seemed to know intuitively that the barbershop door was the way in to a Black man's psyche. "It's a place where positive connections occur," she said.

ALF's Black Men's Project has replicated the success of The Confess Project and Colorado Black men are fortifying the effort. Four of the five speakers were local and the fifth was a Denver celebrity. They all had agreed to share personal stories in order to connect with shop customers as peers.

Support our inclusive, solutions-based journalism so we can bring you more articles like this one.

According to Mental Health America, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) and numerous studies, peer support has a powerful effect on people. It improved quality of life and increases engagement and personal satisfaction. SAMHSA's 2017 "Value of Peers" campaign described interactions between people who struggle and trained peers with similar life experiences as transformative, generating a level of acceptance, understanding and validation not found in traditional doctor-patient relationships. It's a robust, influential connection, kind of like the one between barbers and their customers.

"Black men need to learn that being vulnerable isn't a bad thing. Opening up can bring help and good things our way," said the jovial event M.C., Frank Sinclair. One might say Sinclair is a professional encourager since he hosts two radio shows, "The Be Encouraged Show," on Family Flavors The Slide WBN and "The Encourage-Preneur Show," on KPPF, both in Colorado Springs. He also runs Dream Again LLC, a life-coaching service.

Shop owner Thomas Smith flicked on a trimmer and the sound vibrated across the black-and-white tiled floor. People were attending virtually and ALF's administrative assistant, Katie Cueva, repositioned the laptop to capture a better view of the next speaker.

Kirk Woundy is a representative of NAMI Colorado Springs. He spoke briefly about the organization's efforts over the last 40 years, saying that his door was always open. He praised the vitality of safe spaces like this one and peer volunteers who assist with outreach.

Reverend André "Rev" Summerset of the Solomon Faith Temple filled the room with his large presence and booming voice as he stood. "Mental health comes from who you are," he told the audience. "Everybody is here in this life to help someone." His black t-shirt proclaimed in white letters, "Black King" and "I am who I am."

Rev started attending church as a small boy in Chicago when he learned about the hearty breakfast being offered before the sermon. He even convinced his mother to join him. His story wound through streets and alleys, addiction and homelessness until he realized the truth of one of his mother's sayings, "You can't get it fast or you'll lose it fast." So, he reached out for help even though it went against street culture. "The deeper your roots, the higher you can climb," he said, extending his hands toward the high shop ceiling. His ministry has spanned 40 years.

The fourth man drove the hour from Denver to connect with Midtown's customers. He became a speaker for the NAACP at the age of 15, a fierce poet who co-founded the Slam Nuba team, an author and the executive director of Shop Talk Live Denver. Theo Wilson wore a stylish, gray sport coat and diamond studs in his ears. His charisma and writing talent had helped him win his first-ever poetry slam in 2011 – the National Poetry Slam – and catapulted him to prominence as a TedTalk speaker and host of the "I Was There" television show on History. "[Mental health] is a topic that has governed everything that I've ever done in my life of substance," he said. "It is challenged generationally in my family.... I didn't understand what it meant to grow up underneath the governorship of a man who was dealing with dark forces...."

As a boy, Wilson watched his father deal with severe PTSD from his service in Viet Nam and also saw him journaling to address his mental health needs. Wilson took up the habit, writing until the words on paper matched his turbulent feelings. Poetry came naturally to him as a compelling way to express his life dilemmas and triumphs. From there, he turned to rap and spoken word artistry. He has continued to sharpen his craft, producing the spellbinding performances for which he's known. He concluded with one of his spoken poems entitled, "Powerful."

Paul Wiggins was the final man to speak. He was tall and lanky with a boyish face, a pleasant voice and a doctorate in management. Likely the most educated person present, Wiggins said he had learned to invest in himself mentally and emotionally while he was in the U.S. Air Force and later as a military contractor. He is one of the fortunate who have avoided the pervasive stigma surrounding mental health in the U.S. military.

Servicepeople and veterans can find links to support on many government websites and through healthcare providers, but few military mental health programs are confidential. The Department of Defense's website, Military OneSource, lists links for managing finances, dealing with moving and family separation, recreating, even consulting on adoptions, but only "non-medical counseling" appears as a category in the "Confidential Help" section. Veterans have indicated that regular therapy sessions are noted in personnel files and formal mental health treatment for those with high security clearances can jeopardize careers.

Wiggins' voice quavered slightly as he transitioned into vulnerable peer. "I'm here today to say...as men, as Black men, it is okay to ask for help. It is okay to say, 'I need help, where can I go?' I learned the hard way when I was in the basement with a bottle in my hand and my daughter was upstairs sleeping and I had to stumble my way upstairs and look at her and say, 'This is not who I am. I can't be this man,'" he said.

Enter the barbershop as pressure-relief confessional and low-cost therapeutic ally of secretly struggling Black men.

(left) Summerset and Woundy, (middle) shop owner Thomas Smith, (right) Wiggins, Summerset and Clark. Photos by William Peterson

In a crisis? Call or text 988, the National Lifeline.