By Dr. Nathaniel P. Morris, The New England Journal of Medicine

If a person living on the streets becomes distressed when put in handcuffs, is that due to a mental disorder or does our society suffer from an injustice disorder?

I scroll through the psychiatry consult list and add Mr. C to my list of patients to see. He was transferred from a jail in another county to the jail where I work, where he has never been before, and I’ve been asked to see him for a psychiatric assessment.

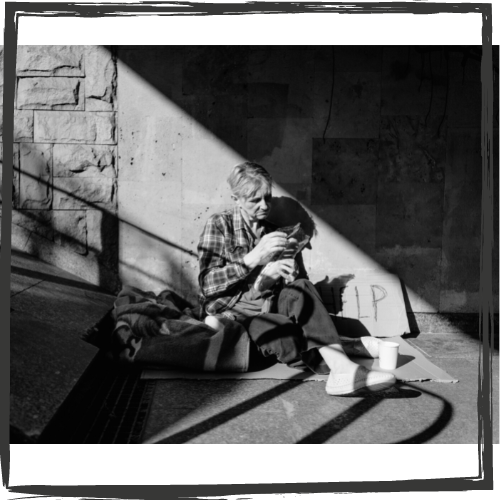

As I review his chart, a pattern slowly emerges. An older Black man, Mr. C has been arrested a few times over the years, typically for vague charges such as trespassing or disorderly conduct that are difficult to interpret. Is he truly menacing to people around him, or is he just trying to survive while living on the streets? He has little history of mental illness or substance use, except for an issue that seems to arise whenever he is brought to jail: he starts yelling that he doesn’t want to live any more.

When he’s incarcerated, Mr. C becomes so distressed that he tears his clothing or sobs loudly throughout the night, to the point where others get upset with him. He has been placed on suicide watch in padded jail cells, sent to emergency departments and seen by various mental health professionals, and usually these symptoms resolve within days after he enters jail or when he’s released.

I sigh, reading in his records the same diagnosis again and again, one that I’ve become simultaneously familiar and disillusioned with: “adjustment disorder.”

According to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, an adjustment disorder manifests in emotional or behavioral symptoms that arise alongside an identifiable stressor and typically resolve as the stressor disappears.

There are various criteria for the diagnosis of an adjustment disorder, and the process includes consideration of cultural and contextual factors that may shape patients’ symptoms. Nonetheless, health professionals tend to make this diagnosis when someone whose condition does not meet the criteria for another mental disorder demonstrates “marked distress that is out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor.”

I recall studying in medical school classic cases of adjustment disorder. For example, a person has difficulty functioning because of depression or anxiety after a divorce. During medical school and residency, I learned that this diagnosis can sometimes be useful for clinicians, allowing us to name patients’ distress and use common language to characterize their clinical presentations after stressful life events.

Yet, in caring for incarcerated patients as a trainee and now as an attending physician, I’ve become troubled by the use of this diagnosis, among others. What does it mean to have a reaction that is “out of proportion” to being placed in shackles? Is there a “normal” way for a person to behave when stripped of freedom and locked in a cell?

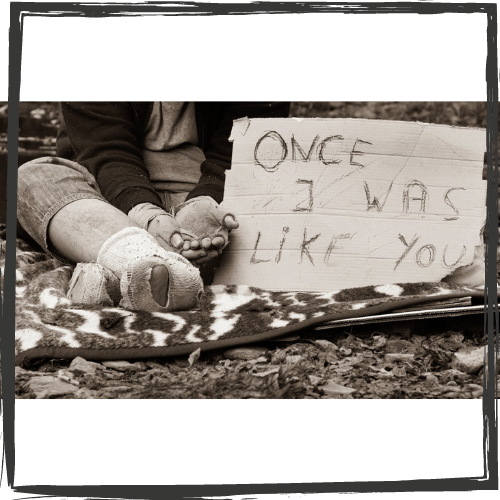

If an older Black man living in poverty on the streets, surrounded by a society that provides him with little assistance and does not seem to care about him becomes distressed when put in handcuffs, does he have a mental disorder? Should he “adjust” to this unjust reality, or does the disorder lie in the systems around him?

A great deal has been written about the dehumanizing nature of incarceration. Less attention has been paid to the ways in which health professionals, and the diagnoses we make, can compound the trauma experienced by people who have been incarcerated.

A woman locked in a cell for 23 or 24 hours a day might fall into such loneliness and despair that she cuts herself to get out of her cell and be sent to the hospital, whereupon physicians and nurses label her as “malingering” and promptly discharge her back to shackles and chains. When a man repeatedly acts out, yelling at staff or kicking his cell door, to protest against the conditions of his confinement, he will too often wind up with a medical chart filled with references to a “personality disorder” and notes on how challenging he is.

The language we use in medicine often fails to do justice to people who are put in cages. Incarcerated people have high rates of mental disorders, substance use disorders and other general medical conditions, yet they are usually not included in the research and field trials that guide diagnostic and treatment practices in the U.S. Even the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which provides estimates of the nationwide prevalence of mental and substance use disorders, does not include jail and prison populations in its data.

As long as national medical organizations and government agencies exclude incarcerated people from research, the language and statistics used by health professionals, policymakers and others will fail to accurately reflect the public health needs of U.S. communities. Including incarcerated people in the studies and surveys that shape national health policy and healthcare practices is essential.

Beyond such additional research, health professionals need to consider not only the ways in which jails and prisons can affect people’s lives but also clinicians’ potential roles in exacerbating the traumatic effects of mass incarceration, poverty, racism and other injustices. Clinicians should recognize that although diagnostic labels can help characterize patients’ health needs and guide treatment approaches, diagnoses can also be harmful, especially when applied haphazardly and without thoughtful consideration of patients’ life circumstances.