Maslow was deeply influenced by the Siksika Nation, but he also was governed by white culture and perspectives

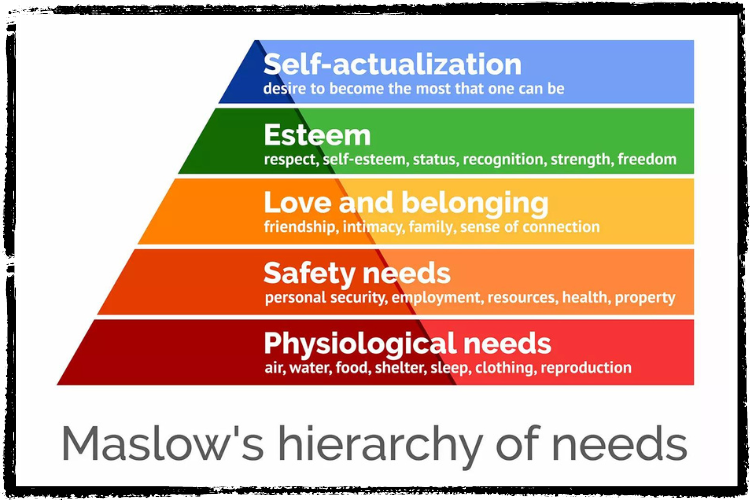

Some months ago, I came across unpublished papers by Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist and psychology professor who became one of the most influential human motivation theorists of the 20th century. He stated that humans act according to a "hierarchy of needs" with physiological needs being the most essential and consuming and self-actualization occurring only after all other needs are met.

My friend, Roberto Carlos Rivera, executive director of Alliance for the 7th Generation and a GatherFor board member, told me more: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs may have been inspired by the Siksika (Blackfoot) way of life.

I learned Maslow spent six weeks living at Siksika — which is the name of the people, their language and their reservation — in the summer of 1938. His time there upended some of his early hypotheses and possibly shaped his revolutionary theories.

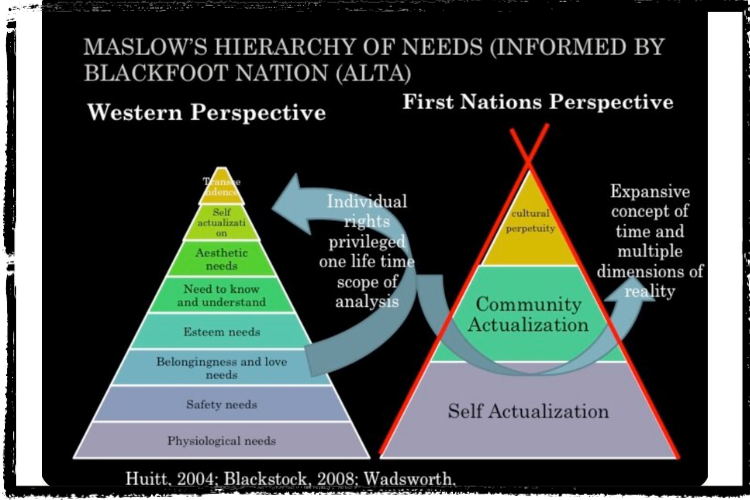

Maslow has been criticized for misrepresenting the Siksika worldview. He characterized their philosophy as a type of community building that leaves no one behind. Actually, according to researchers Ryan Heavy Head (also known as Ryan FirstDiver) and the late Narcisse Blood, members of the Siksika Nation, Siksika people believe self-actualization is a basis for community actualization which is, in turn, a basis for cultural perpetuity, exemplified by the top of their tipis.

What Maslow encountered at Siksika

According to Heavy Head and Blood, a 30-year-old Maslow arrived at Siksika to test the universality of his theory that social hierarchies are maintained by dominance of some people over others. However, he did not see dominance in Siksika society. Instead, he discovered astounding levels of cooperation, minimal inequality, restorative justice, full bellies and high levels of life satisfaction. Heavy Head said Maslow estimated that “80-90 percent of the Siksika had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in five to 10 percent of his own population.”

Heavy Head shared with me on the phone, “Maslow saw a place where what he would later call 'self-actualization' was the norm.” This observation, Heavy Head continued, “totally changed Maslow's trajectory.” For readers wondering about self-actualization, Maslow offered this definition influenced by Kurt Goldstein: “This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.” The word itself does not exist in the Siksika language, but the closest word is niita’pitapi, which Heavy Head said means “someone who is completely developed, or who has arrived.”

Deeply curious about the stark difference between Siksika culture and his own, Maslow first sought out positive deviants, or unusually successful individuals. He started with the wealthiest tribal members. In his writing, he said that for the Siksika, “wealth was not measured by money and property but by generosity. The wealthiest man in their eyes is one who has almost nothing because he has given it all away."

Maslow witnessed a Siksika “Giveaway” ceremony in his first week. During the Giveaway, members of the tribe arranged their tipis in a circle and publicly piled up all they had collected over the last year. Those with the most possessions told stories of amassing the goods, then gave everything to those in greater need. By contrast, as shared by Maslow’s biographer Edward Hoffman, Maslow observed different qualities in his own culture.

"Maslow was shocked by the meanness and racism of the European-Americans who lived nearby. As he wrote, 'The more I got to know the whites in the village, who were the worst bunch of creeps and bastards I’d ever run across in my life, the more it got paradoxical.'”

Per Heavy Head and Blood's research, then Maslow continued his investigation by looking into negative deviants, lawbreakers. In his writing he said, "The [Siksika] didn’t peg them as deviant. A person who was deviant could redeem themselves in society’s eyes if they left that behavior behind."

Maslow wondered whether the answer to producing high self-actualization might lie in child-rearing. He found that children were raised with great permissiveness and treated as equal members of Siksika society, in contrast to a strict, disciplinary approach found in his own culture. Despite having great freedom, Siksika children listened to their elders and served the community from a young age, stated Heavy Head and Blood.

According to Heavy Head, witnessing the qualities of self-actualization among the Siksika and diving into their practices led Maslow to deeper research into the journey to self-actualization, and the eventual publishing of his famous Hierarchy of Needs concept in his 1943 paper.

Differences between Maslow’s theories and Siksika beliefs

Heavy Head said while there are strong belief systems and long-standing traditions in place, the Siksika don’t have a “model” for their worldview neatly codified like Maslow’s. To help contrast Western and First Nations' worldviews, Dr. Cindy Blackstock of McGill University, herself a member of the Gitxsan tribe, created an illustration.

Blackstock showed there is great diversity among First Nations, but her diagram (above) captures some of the similarities she found in her research.

Self-actualization

Maslow wondered, “How do we become self-actualized?” Many First Nation communities might be more likely to believe that we arrive on the planet already so. Heavy Head explained the difference through the analogy of earning a college degree. In Western culture, you earn a degree after paying tuition, attending classes and proving sufficient mastery of your area of study. In Siksika culture, “it’s like you’re credentialed at the start," he said. "You’re treated with dignity for that reason, but you spend your life living up to that.”

Seeing people as inherently wise involves trust and space, perhaps manifested by the lenience observed by Maslow of Siksika parents with their children. For many Indigenous peoples, according to Heavy Head, self-actualization is drawn out of an inherently sacred being who is imbued with a spark of divinity. Education, prayer, rituals, ceremonies and individual experiences invite the expression of this sacred self into the world, he said.

Community actualization

As Maslow witnessed in the Siksika Giveaway, many Indigenous cultures see the work of meeting basic needs, ensuring safety and creating the conditions for the expression of purpose as a community responsibility, not an individual one. Heavy Head explained that such communal cooperation is especially important for the Siksika because of their relationship to place, an aspect Maslow entirely omitted in his theories:

"The one thing that [Maslow] really missed was the Indigenous relationship to place. Without that, what he’s looking at as self-actualization doesn’t actually happen. There’s a reason people aren’t critical of their tribe: you’ve got to live with them forever."

In other words, having your life bound up with those around you for its whole duration can support creating a culture of generosity, trust, and cooperation, rather than one of inequality and individualism.

Cultural perpetuity

The skill to nourish a community-wide family, keep each person fed, live in harmony with the land and minimize internal and external conflicts is handed down from generation to generation by First Nations peoples, said Blackstock. Because knowledge can vanish as people pass on, each generation sees it as their responsibility to perpetuate their culture by adding to the people's communal wisdom, passing on ancestral teachings to children and grandchildren. Blackstock explained:

"First Nations often consider their actions in terms of the impacts of the 'seven generations.' This means that one’s actions are informed by the experience of the past seven generations and by considering the consequences for the seven generations to follow."

Many First Nations have developed both formal rituals and informal apprenticeships for the transfers of wisdom from elders to youngsters to ensure the community is able to support self-actualization and community actualization in perpetuity.

Why haven’t we heard about the Siksika worldview?

Although Maslow saw full bellies, low inequality and high rates of self-actualization, why didn’t he tell the world so we could all learn from the Siksika? He may have faced dismissal if he had publicized their teachings.

Dr. Richard Katz, author of Indigenous Healing Psychology: Honoring the Wisdom of First Peoples, Harvard professor and Maslow’s friend, spoke about this point in a podcast conversation. He postulated that Maslow may have been concerned that elevating Siksika teachings might diminish the validity of his own ideas. Blackstock indicated that such racist barriers to Indigenous contributions remain in academia.

By offering compelling alternatives, Indigenous worldviews also pose a threat to our status quo. Lakota Medicine Man John Fire Lame Deer offers one poignant contrast between the world he grew up in and the world of “the white man”:

"Before our white brothers came to civilize us we had no jails. Therefore, we had no criminals. You can’t have criminals without a jail. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves. If a man was so poor that he had no horse, tipi or blanket, someone gave him these things. We were too uncivilized to set much value on personal belongings. We wanted to have things only in order to give them away. We had no money, and therefore a man’s worth couldn’t be measured by it. We had no written law, no attorneys or politicians, therefore we couldn’t cheat. We really were in a bad way before the white men came, and I don’t know how we managed to get along without these basic things which, we are told, are absolutely necessary to make a civilized society."